Year XXXVIII, Number 3, November 2025

Which Reform for the United Nations Security Council?

Daniele Archibugi

Professor at the Universitas Mercatorum in Rome and at Birkbeck College, University of London. Associate researcher at the Italian National Research Council.

Marco Cellini

Researcher at the Institute for Research on Population and Social Policies of the Italian National Research Council.

Azzurra Malgieri

Researcher at the Institute for Research on Population and Social Policies of the Italian National Research Council.

Is the Security Council Still needed?

The Security Council (UNSC) has never played the ambitious role that the architects of the United Nations had intended since it has failed to prevent wars and ensure international stability. Yet, it has served a useful purpose in world politics as a clearinghouse and has been the institutional forum where the great powers could take a stand before public opinion. If the UNSC fails to resolve conflicts, other channels of international crisis management are inevitably activated, such as superpower summits, secret diplomacy, or even outright wars. It is therefore in the interest of international peace and stability that the UNSC can best perform its function1.

Many informal changes have been introduced in the functioning of the UNSC2, but no serious reform has been implemented so far. The use and abuse of the veto, the lack of implementation of the resolutions adopted and the poor attention paid to peripheral conflicts have led to a lack of authority of the UNSC as the central institution for the management of international conflicts and crises.

We conducted a study for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation in which we attempted to connect the numerous proposals for reform of the UNSC with the actual voting profiles, and the results are here summarized3.

How to Reform the UN Security Council?

The reform of the UNSC has long been discussed in diplomatic, academic and civil society forums. The General Assembly itself has established an “Open-ended Working Group on the Question of Equitable Representation on and Increase in the Membership of the Security Council”4. Given that the Working Group was established in 2008, and there have been so many diplomatic talks since 1991, but it has not managed to provide any shared recommendation, it is not surprising that at the UN Secretariat Building it has been nicknamed the “Never-ended Working Group”.

The lack of consensus among member states and, in particular, among the P5, has prevented any substantial change. The need for an update of its structures and decision-making methods is evident, especially considering the geopolitical transformations that have occurred since the end of the Cold War.

The main reform directions - the expansion of representation, the modification of the right of veto, the strengthening of accountability and the involvement of regional actors – are discussed below.

Expanding Representation

One of the most perceived problems of the Council is its lack of representativeness. Currently, the five permanent members (P5) – France, the United Kingdom, Russia and the United States – reflect a geopolitical order dating back to the Second World War. Although the number of elected members (E10) was increased in 1965, the Council still does not fairly represent the contemporary world. The main imbalances are:

• Geographic representation: Africa, with 54 UN member states, has no permanent seats, while Asia, home to nearly 60% of the world’s population, is underrepresented relative to the region’s demographic and economic weight.

• Economic representation: Japan and Germany, the world’s third and fourth largest economies respectively, are not permanent members, despite their financial contribution to the United Nations being greater than that of the P5 Britain, France and Russia.

• Demographic representation: India, the world’s most populous country, does not have a permanent seat, unlike countries with significantly smaller populations.

This has led to a new Olympic race: quite a lot of states are running to secure a permanent seat. The expansion of the Security Council could take place in various ways, but the main debate is whether the new members should have the same status as the P5 or not. Over the years, several proposals have been presented including by the so-called African Group, CARICOM countries, Group of 4, Group of Arab States, L69 Group, and most recently the Italian-led proposal United for Consensus. The reform proposals presented so far can be divided into three main categories:

• Limited enlargement model: This approach involves adding new permanent members without veto power. The Group of 4 (Brazil, Germany, India and Japan) has proposed this solution, arguing that their entry would strengthen the legitimacy of the Council without increasing the risk of decision- making paralysis.

• Enhanced rotation model: It is proposed to introduce seats with longer terms than the current two years, allowing immediate re-election. This would ensure greater coherence.

• Regional representation model: An innovative idea suggests assigning some permanent seats not to individual states, but to regional blocs (for example, one seat each for the African Union or ASEAN, in addition to the European Union). This model would reduce conflicts between national candidates and strengthen regional coordination on security issues.

Would enlargement change the voting results? The enlargement proposals are understandable and with the changes in the global geopolitical structure, including the funding that individual states pay into the Organization’s coffers, there is a desire on the part of many governments to have a more active role in the“control room”of global politics.

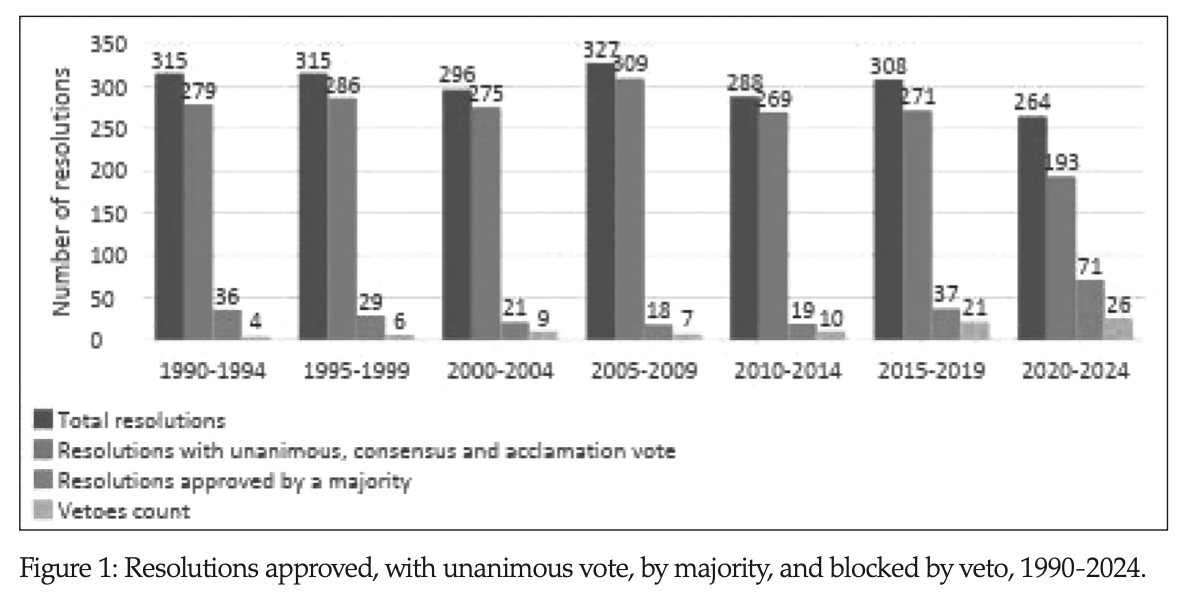

But each possible reform of the UNSC cannot ignore the real voting patterns. Figure 1 shows what the votes have been since 1990, when the Cold War ended and another historical era began.

The first significant fact is that most of the resolutions were approved, even unanimously. Only a small number of resolutions had votes against. And even lower is the number of resolutions that were rejected due to the veto of one of the permanent members.

Of course, not all resolutions have the same political weight. It is certainly easier to achieve unanimity on resolutions that are not onerous. The fact that quantitatively the cases of disagreement are few, confirms that international rivalry is concentrated on a few issues. Since 1990, the veto has been used mainly on issues related to the Middle East, the protection of allied regimes and geopolitical competition between great powers.

• The United States has vetoed primarily resolutions concerning Israel and Palestine.

• Russia has used the veto to protect its interests in Syria and Ukraine.

• China has only recently begun to veto, and almost always in line with Russia.

• France and the United Kingdom have not used the veto since the end of the Cold War.

None of the enlargement proposals would have substantially altered these voting patterns.There is not much difference if a resolution is blocked with a 14-0-1 result (14 in favour, 0 abstention and 1 vote against) or with a 26-0-1.

Can the power of veto be limited?

The real issue, then, is the ability to prevent resolutions from being blocked and, secondly, to be able to get them to be implemented. Here are some of the proposals.

• Thematic limitation: Some propose to exclude the use of the veto for crimes against humanity, genocide and other serious violations of international law.

This would reduce the P5’s ability to block urgent humanitarian interventions.

• Reinforced veto: Another proposal suggests that the veto can be exercised if at least two permanent members oppose a resolution. This would discourage the use of the veto for national interests.

• Qualified majority override: The General Assembly could be empowered to invalidate a veto if a large majority of member states oppose it.

• Justification requirement: The 2022 General Assembly resolution required that if a P5 vetoes, it must justify its decision in a session of the General Assembly. This measure, although not binding, aims to make the use of the veto more costly in terms of international reputation.

Strengthening transparency, representativeness and accountability of elected members

Veto power is certainly not the only problem with the UNSC. There is also a lack of transparency in decision-making processes and poor accountability for elected members (E10). Since elected members are not subject to any formal accountability mechanism to their regional groups or the international community, it is not clear whether they are acting in representation of the general global interest, the interests of the constituency they represent, or merely their own state.

The literature highlights two problems regarding the behavior of E10s.

• States that run for the UNSC try to gain votes by using economic aid provided to developing countries as a negotiating tool5. Rich and powerful states campaign by promising money and thus have a better chance of being elected than poor and weak states.

• The voting behavior of the E10 does not correspond to the preferences of the states in the regional constituencies, as expressed in the votes at the General Assembly6. The E10 therefore follow their own preferences and not those of the region they represent.

To improve transparency, a system could be introduced where:

• States applying for an elective seat (E10) must submit a public work programme before their election.

• Elected members must provide an annual report on their activities and performance.

If the E10 met these criteria, they could have greater authority within the UNSC and be able to more effectively counteralt the interests of the P5.

Can the composition and procedures of the Security Council be changed?

Any change would require a very broad international consensus, in a context in which the main global actors often have divergent interests. In fact, every “formal” reform is regulated by Art. 108 of the Charter and requires that an amendment to the Charter must be adopted by the Assembly with a majority of 2/3 and subsequently ratified by 2/3 of the member states, including the P5. A “substantial” revision should follow the procedure outlined in Art. 109, which is even more complex and has never been put into practice so far.

However, combining the enlargement proposals with the votes in the body shows the following aspects:

• Expanding the membership of the UNSC to include other states may help make the body more representative, but it would not solve the root cause of the fact that crucial decisions are often blocked by the veto of a single state.

• Making it more difficult and costly to use the veto power would help make the UNSC more effective and authoritative.

• It is possible to strengthen the transparency, representativeness and accountability of elected members (E10), ensuring that they can be an effective counterbalance to permanent members.

• It is necessary to overcome the idea that the members of the UNSC should only be states. The first candidates could be regional organizations, such as the European Union, ASEAN, African Union, Organization of American States and Arab League, encouraging plurality and increasing authority. This will help to increase regional collaboration and stability and will possibly reduce competition to be elected in the E10.

It is only a remote hope that the veto can be abolished. The possibility of reducing and, in the long run, eliminating the P5 veto is voluntary, and can only be achieved if the P5 decide not to use it. The only hope is that the United States, Russia and China follow the example of France and the United Kingdom, which have not used the veto in recent decades.

The path towards global democracy has many and varied components and involves a wealth of international organizations, treaties and agreements7. But certainly one of the most important gridlock represented by the UNSC cannot be ignored: as long as the UN executive body competent on peace and security is blocked by the veto, it will be difficult to achieve truly democratic global governance

1. Archibugi, D., The Global Commonwealth of Citizens. Toward Cosmopolitan Democracy, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2008.

2. Hosli, M.O. e Dörfler, T., 2019. Why is change so slow? Assessing prospects for United Nations Security Council reform. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 22(1), pp.35-50; Gifkins, J., 2021. Beyond the veto: Roles in UN Security Council decision-making. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 27(1), pp.1-24.

3. For a full analysis, see Archibugi, D., Cellini, M., Malgieri, A. 2025. The Reform of the UN Security Council: What Are the Issues?, Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 31(2), 137-162, https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-03102003.

4. See the UN General Assembly webpage at https://www.un.org/en/ga/screform/

5. Dreher, A., Sturm, J.-E., & Vreeland, J. R. (2009). Development aid and international politics: Does membership on the UN Security Council influence World Bank decisions? Journal of Development Economics, 88(1), 1–18; Reinsberg, B., 2019. Do countries use foreign aid to buy geopolitical influence? Evidence from donor campaigns for temporary UN Security Council seats (No. 2019/4). Wider Working Paper.

6. Lai, B. and Lefler,V.A., 2017. Examining the role of region and elections on representation in the UN Security Council. The Review of International Organizations, 12, pp.585-611.

7. Levi, L., Finizio, G., & Vallinoto, N., The Democratization of International Institutions, London, Routledge, 2014; Koenig-Archibugi, M. The Universal Republic: A Realistic Utopia?, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2024.